1.6K

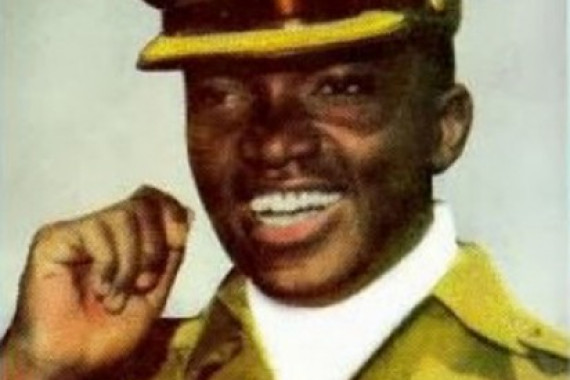

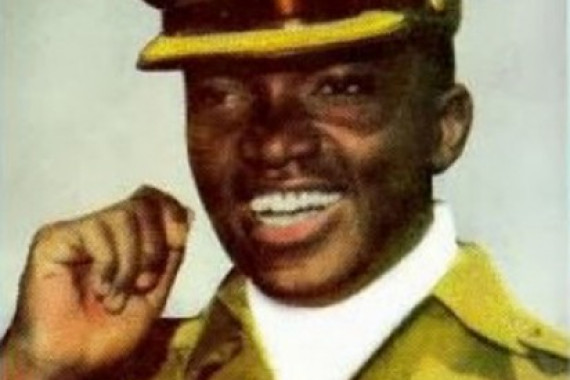

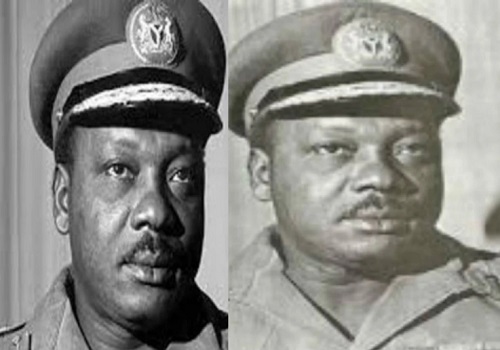

To take you back to memory lane and refresh you history knowledge, here is the story of how Major Chukwuma Nzeogwu, who was a young army officer, plotted the military coup of January 15, 1966 which led to the death of many senior Nigerians.

The story of the Nigerian civil war cannot be completely told without the mention of the name, Major General Kaduna Chukwuma Nzeogwu. Reasons being that he is said to be the leading brain behind the first military coup in January 1966 which was tagged an ‘Igbo coup’ leading to a counter-coup in June of the same year, the aftermath of which led to the secession of the Biafran territory and subsequent war.

Patrick Chukwuma Kaduna Nzeogwu hailed from the then Mid-western region town of Okpanam, near Asaba in the present day Anioma area of Delta state. He was born in 1937 in Kaduna, Kaduna state. He attended Saint Joseph’s Catholic Primary School in Kaduna for his elementary education and for his secondary education he attended the competitive Saint John’s College in Kaduna.

In March 1957 after his secondary education, Nzeogwu enlisted as an officer-cadet in the Nigeria Regiment of the West African Frontier Force and proceeded on a 6-month preliminary training in Ghana, then Gold Coast. He completed his training in Ghana by October 1957 and headed on to the Royal Military Academy, Sandhurst where he was commissioned as an infantry officer in 1959. He later underwent a platoon officer’s course in Hythe and a platoon commander’s course in Warminster.

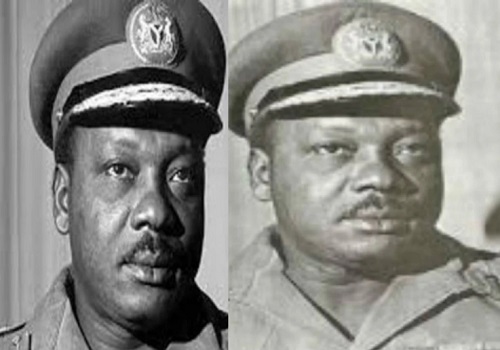

After receiving all the trainings, he returned to Nigeria in May 1960 shortly before independence, and was posted to the 1st Battalion in Enugu where Major Aguiyi-Ironsi was the second-in-command under a British officer. He was later re-posted to the 5th Battalion in Kaduna, the land of his birth, where he became friends with Olusegun Obasanjo. His Hausa colleagues in the Nigerian army gave him the name Kaduna because of his affinity with the town.

After serving in The Congo in 1961, Nzeogwu was assigned as a training officer at the Army Training Depot in Zaria for about 6 months before getting posted to Lagos to head the military intelligence section at the Army Headquarters where he was the first Nigerian officer.

The forerunner of the Nigerian army intelligence corps (NAIC) was the field security section (FSS) of the Royal Nigerian army, which was established on 1 November 1962 essentially as a security organization whose functions included vetting of Nigerian army personnel, document security and counter intelligence. Major Nzeogwu was the first Nigerian officer to hold that appointment from November 1962 to 1964. As a military intelligence officer, he participated in the treasonable felony trial investigations of Obafemi Awolowo and other Action Group party members.

Nzeogwu was believed to have stepped on toes of army officers in his capacity as a military intelligence officer and even clashed with the minister of state for the army, Ibrahim Tako Galadima, also known as Galadima Bida. Consequently, he was posted to the Nigerian Military Training College in Kaduna where he became chief instructor.

Lt-Col Patrick Anwunah described Nzeogwu as “a radical and an inwardly insubordinate young officer who was full of his own ideas and probably thought he had the answers to all problems. His statements and comments at that time gave me the impression that he could become insubordinate as he had no regard for senior officers” giving the impression that in his quest for what he perceived to be just, he did not give two thoughts about offending people.

In the early hours of January 15, 1966, at the young age of 29, Nzeogwu led a group of soldiers on a pre-planned but secret military exercise to attack the official residence of the Premier of the North, Sir Ahmadu Bello in a bloody coup. The end of the coup saw the murder of Premiers of Northern and Western Nigeria.

The Prime minister, a federal minister, two regional premiers and top army officers from the northern and western regions of the nation were brutally murdered. The premier of the eastern region (where most of the plotters came from), the Igbo president of federation and the Igbo army chief were the only notable individuals spared. These factors led to the general conclusion that it was an Igbo coup.

In his radio broadcast to announce the suspension of the democratic regime and civilian rule, he stated that their aim was to “establish a strong united and prosperous nation, free from corruption and internal strife” and described the collective enemies of the country which they were up against to include “the political profiteers, the swindlers, the men in high and low places that seek bribes and demand 10 percent.

“Those that seek to keep the country divided permanently so that they could remain in office as ministers or VIPs at least, the tribalists, the nepotists, those that make the country look big for nothing before international circles, those that have corrupted our society and put the Nigerian political calendar back by their words and deeds.”

Notably, he did promise in his speech that every law abiding citizen would enjoy all the basic freedoms especially freedom from fear of oppression. “We promise that you will no more be ashamed to say that you are a Nigerian,” he stated emphatically.

However, the officer who took over the administration of the country, General Aguiyi Ironsi, arrested Nzeogwu days after he assumed power while he was in the company of Lt. Col. Conrad Nwawo. This was not sufficient reasons for the Northerners to conclude that the coup might have been just Nzeogwu’s idea, as a counter coup still occurred months later, this time with countless Igbo civilians and military officers being brutally murdered. The ensuing crisis led to the secessionist move of the Biafran geographical entity on May 30, 1967, and consequently the civil war.

In an interview with Dennis Ejindu in 1967, Nzeogwu explained that the coup being perceived as one sided was because the people who had been stationed in the South with Major Emmanuel Ifeajuna in charge, grew cold feet at the eleventh hour. According to him: “We were five in number, and initially we knew quite clearly what we wanted to do. We had a short list of people who were either undesirable for the future progress of the country or who by their positions at the time had to be sacrificed for peace and stability of the nation.

“Tribal considerations were completely out of our minds at this stage. But we had a set-back in the execution. Both of us in the North (himself and Major T. C. Onwuatuegwu) did our best. The Mid-west was never a big problem. But in the east, our major target, nothing practically was done. He (Ifeajuna) and the others let us down.”

As revealed by Nzeogwu also in the same interview with Ejindu, there was no reason to be enthusiastic about secession. Shortly before the war, Nzeogwu was released from close observation by Lt. Colonel Odumegwu Ojukwu, and asked to go into battle on the side of the Biafrans.

On July 29, 1967, Nzeogwu, who had been promoted to the rank of a Biafran Lt. Colonel, was trapped in an ambush near Nsukka while conducting a night reconnaissance operation against federal troops of the 21st battalion under Captain Mohammed Inuwa Wushishi. He was killed in action and his corpse was subsequently identified by Lieutenant Abdullahi Shelleng who ordered that it should be stored firstly in the University of Nigeria campus at Nsukka.

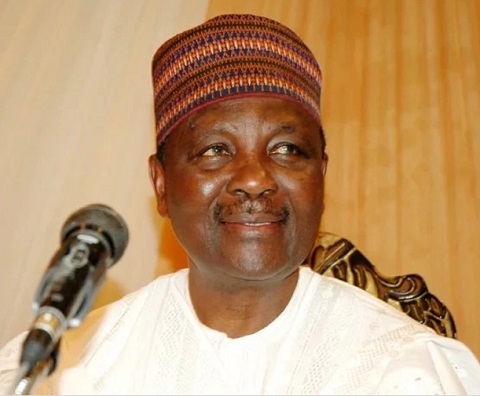

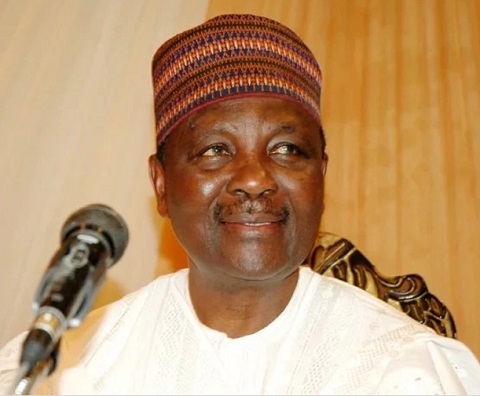

The corpse was later sent to 1 division headquarters in Makurdi where the 1 division commander, Colonel Mohammed Shuwa, informed the head of state Major-General Gowon. Despite the fact that Nzeogwu was now technically an enemy soldier killed in combat against the Nigerian army, Gowon ordered that Nzeogwu’s body be flown to Kaduna and buried with full military honours – even as the war raged on in the eastern region.

He had been insistent that until a true federal system was worked out, a confederation could still work for Nigeria. He was so hopeful about the country Nigeria that he not completely ruled out secession of any region as impossible. “As you know there is too much bitterness at present in the country, and in the past people had imagined that they could conveniently do without one another. But the bitterness will clear in the end and they will find that they are not as self-reliant as they had thought. And they will long to be together.

“In the present circumstances, confederation is the best answer as a temporary measure. In time, we shall have complete unity. Give this country a confederation and, believe me, in ten or fifteen years the young men will find it intolerable, and will get together to change it. And it is obvious we shall get a confederation or something near it. Nothing will stop that.”

Such strong views on secession did not make him best of friends with Ojukwu as they rarely saw eye to eye on the issue. Relations between Ojukwu and Nzeogwu deteriorated further as Nzeogwu made no secret of his desire for a united Nigeria. Even though war between Nigeria and Biafra was imminent, in April 1967 Nzeogwu was suspended from all military activities by Ojukwu.

The immediate pretext was Nzeogwu’s involvement in a battle simulation military training exercise in Abakaliki and other towns in the eastern region. Recalling that Nzeogwu had turned the night time training “Exercise Damissa” into a full blown coup the previous year, Ojukwu banned all such further exercises. Relations between Ojukwu and Nzeogwu got bad enough for Ojukwu to consider putting Nzeogwu back in prison.

Writing a letter to his friend Olusegun Obasanjo on June 17, 1967, Nzeogwu confessed: “You have no doubt heard a lot of rumours about my relations with Ojukwu. We obviously see things quite differently after what he did to my supporters in January 1966. He is also worried about my popularity among his own people. I was to be put back in prison, but he was afraid of repercussions. Right now I am not allowed contact with troops nor am I permitted to operate on the staff. One gentleman’s agreement we have is that I can carry on with whatever pleases me.”

A personality cult bordering on hero worship grew up around him in the eastern region and he was being feted as an immortal indestructible warrior. Although Ojukwu gave Nzeogwu the Biafran rank of Brigadier, he was not given any formal command in the Biafran army. Frustrated at his exclusion from military duties, Nzeogwu took to informal ad hoc guerilla raids against the federal army. He would impulsively conscript other soldiers to join him during these raids.

Nzeogwu was admired and feared in equal measure. He was admired for his intelligence, warmth and charm. He was feared because of his suicidal courage. Junior Biafran foot soldiers were reluctant to be conscripted by Nzeogwu. Conscription by Nzeogwu meant being taken to the front line and faced with grave danger. Nzeogwu was brave enough to cross behind enemy lines, carry out reconnaissance and engage the federal army in close quarter combat.

Even in death, Nzeogwu was still respected by federal and northern troops. Domkat Bali referred to him as “a nice, charismatic and disciplined officer, highly admired and respected by his colleagues. At least he was not in the habit of being found in the company of women all the time messing about with them in the officers mess, a pastime of many young officers then. We believed that he was a genuine patriotic officer who organised the 1966 coup with the best of intentions who was let down by his collaborators.

“If we had captured him alive, he would not have been killed. I believe he probably would have been tried for his role in the January 15 coup, jailed and probably freed after some time. His death was regrettable.” Five decades after his death, there is still yet to be a consensus on whether he was a hero or felon.

Source: Naij.com